Workforce Wrap Up: August Edition

Labor market slowdown, growing inequality, and presidential candidate economic proposals

By: Jomayra Herrera

Welcome to Back to School and Pumpkin Spice Latte Season! I can’t believe it is already September.

It’s time for August’s Workforce Wrap Up. If you’re new here, Workforce Wrap Up aims to give a quick 10-minute download of interesting highlights that happened in our labor market / economy in the past month.

This month, we continue to see the trend of a slowing labor market, stabilizing inflation, and some worrying signs for the average consumer. Every day, it seems more likely we will get a rate cut at the upcoming September meeting. In this issue, we also cover the presidential candidates economic plans.

So with that, let’s dig in:

The labor market continues to slowly cool down - employment increased by 142,000 in August, job openings declined, and layoffs ticked up.

Job gains occurred in construction and healthcare with each adding 24,000 and 31,000 jobs, respectively. Notably, that is half the average monthly gain of 60,000 over the prior 12 months for healthcare.

June and July employment was revised down by 61,000 and 25,000, respectively.

Job gains over the past three months averaged 116,000 per month. In the first three months of 2024, the economy added 269,000 jobs on average.

Average hourly earnings increased by 0.4 percent to $34.21, they have grown by 3.8 percent YoY.

Job openings decreased by 237,000 in July, bringing down the number of openings as a share of total employment down to 4.6% from 4.8%. This is the lowest rate since December 2020. The ratio of open jobs per unemployed worker is now down to 1.1 And the number of layoffs and discharges increased by 202,000, hitting their highest total for the month in 15 years.

The US created 818,000 fewer jobs in the year through March than initially estimated, indicating the employment was slowing down before we even realized

This was the largest downward revision in 15 years. This means that US added 174,000 jobs every month up to March compared to an average of 242,000 before.

Professional and business services accounted for nearly half of the downward revision, but other industries, including leisure and hospitality, manufacturing, and retail trade were impacted too.

What accounts for the huge discrepancy? Economists state it could be issues related to adjustments for the creation and closure of businesses (typically BLS makes adjustments but their numbers may be off in a post-pandemic economy), decreased response rates on their monthly surveys, and how unauthorized immigrant workers are counted (the QCEW report, which is what the revision is based off, relies on unemployment insurance records which undocumented immigrants can’t apply to).

So what does this mean for the future of the economy? Well as you’re reading through predictions, a new report suggests economic forecasters are pretty accurate in the short-term but too overconfident in their long-term predictions

This piece by the New York Fed analyzed the Philadelphia Fed’s Survey of Professional Forecasters from 1982 to 2022. They looked at not just how accurate the forecasters were but also whether they had appropriately lage error bands around their forecast.

They found that for time periods less than a year, forecasters were generally under confident so they had wider error bands than needed. But for longer periods, they were significantly overconfident.

In short, we’re pretty good at predicting what’s coming right ahead of us but we have a much harder time making sense of undercurrents that drive longer term trends and also predicting the unexpected.

In other news, new research shows the housing market was hit particularly hard by the increase in rates. But it’s starting to show some signs of improvement.

A new paper argues that mortgage rates were pushed even higher by the Federal Reserve through channels beyond just interest rate policy decisions.

In the beginning of the pandemic, the Fed purchased trillions of dollars worth of mortgage-backed securities as part of its quantitative easing program, effectively funneling cash to homebuyers. Banks also ramped up their mortgage lending and purchases of MBS in 2020-21.

Though, as you can imagine, as rates rose, both the Fed and banks decreased their MBS holdings significantly. The Fed alone drained its holdings by $400BN.

The impact? The spread between the 10-year Treasury yield and average consumer mortgage rate was only 1.5% in May 2021, but nearly twice as large in 2023. Mortgages were hit twice as hard due to the fact that banks and fed bought so much of them during 2020-21 and when monetary policy reversed course they caused mortgage rates to rise and the spread to widen.

That said, in more positive news, mortgage rates seem to be showing signs of decline.

Unfortunately, there are serious questions around whether an average American can even afford to buy a home these days with the average down payment amount increasing significantly and the housing affordability index deteriorating.

Americans born into low-income families are doing worse than prior generations.

A new analysis from the Census Bureau and Opportunity Insights measured intergenerational mobility at the country level. They compared average household income at age 27 for Americans born to low income families in both 1978 and 1992.

They found that in 38 of the 50 biggest U.S. metros, Americans born to low-income families in 1992 were doing worse at age 27 than those who were born in 1978.

There were a few outliers, such as Brownsville, TX which saw a ~$2K increase in income for those born in 1992. Cities like Tampa, DC, and Philadelphia saw the largest drops.

They also found that the white-Black earning gaps for children from low-income families decreased by 30%. Class gaps grew but race gaps shrank and this was true across other outcomes such as educational attainment, standardized test scores, and mortality rates.

Most interestingly, they found that outcomes improve for children who grow up in communities with increasing parental employment rates. Outcomes are most strongly related to the parental employment rates of peers they are more likely to interact with, suggesting the relationship between children’s outcomes and parental employment rates is mediated by social interaction.

Inequality among high and low income workers is widening

A new study by the SF Fed shows that wealth increased significantly across all income levels during the pandemic, helping to keep consumer spending up even in the face of inflation. But those savings have now dried up, especially for lower-income families.

The study found that at the peak in 2021, the top 20% of households accumulated $1 trillion more in liquid wealth than otherwise would've been the case without the pandemic. Middle and lower-income Americans built up an additional $270 billion.

That wealth dried up for the bottom 80% by late 2021 but it didn’t dry up for the top 20% until a year later. Why? The top 20% invested more in higher interest bearing assets.

At the beginning of 2024, liquid wealth for the rich was 2% lower than pre-pandemic but the bottom 80% had 13% less.

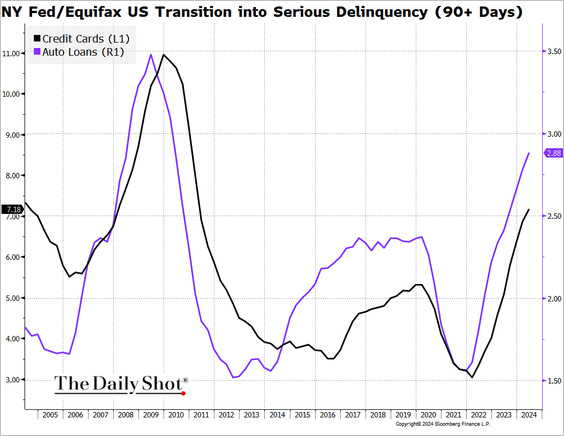

The depletion of pandemic-era savings is being felt in lower savings rates and higher delinquency rates, especially for lower-income consumers.

The top quintile income earners now hold 71% of net wealth as of Q1 2024.

And to add to this, after rapid acceleration in wage growth for “lower skilled” workers, we are starting to see a slow down especially relative to “higher skilled” workers.

Presidential candidate economic proposals are firming up and economists are starting to speculate on the implications of them

The Harris plan includes:

Tax cuts for middle-class families, including a $6,000 child tax credit for families during the first year of a kid's life.

Expanding the earned income tax credit for lower income adults without families.

A $25K down payment support for homebuyers and tax incentives for businesses to encourage the construction of 3 million more housing units.

A ban on price-gouging on food and groceries (it is unclear how this would be implemented)

$35 cap on insulin prices and $2K cap on out of pocket costs for all prescription drugs.

Eliminate taxes on tips for service workers.

A $50K tax deduction for small businesses to help with startup costs.

The trump plan includes:

Reduce the corporate tax rate from 21% to 15% for companies that manufacture products in the U.S.

Permanently extend tax cuts he signed into law while in office in 2017.

Eliminate taxes on tips for service workers.

End income taxes on social security benefits.

Implement double-digit tariffs across the board on all imports and higher targeted tariffs on Chinese goods.

Goldman economists crunched the numbers to predict how each candidate’s proposal would impact the economy.

They found that a Trump win (either divided government or Republicans control both houses of Congress) would result in a 0.5 percentage point decrease in GDP in the second half of 2025 before fading in 2026. This assumes higher tariffs and tighter immigration policies would offset any positive impact from lower taxes.

A Harris win (assuming the Democrats control both the House and the Senate) would lead to a very slight increase to GDP between 2025 and 2026. With a divided government, any policy change would be small and neutral in impact.

An analysis from the Penn Wharton Budget Model found Trump’s proposals would increase national debt by $5.8 trillion over 10 years, while Harris’ would cost $1.2 trillion. If policies are scored using “dynamic pricing” or reflecting the increased tax revenue from additional economic activity the gap shrinks a bit to $4.1TN and $2TN, respectively.

That’s all for this month! See you in October for spooky (or hopefully not so spooky) season.