The Elite Abdicated

How the loss of standards turned freedom into shame

By: Maria Salamanca and Jomayra Herrera

When we wrote You aren’t Kenough, but We Are: Finding Purpose in an “I” Society last year, we promised a Part II where we would share our ideas for new “Engines of Purpose.”

We wish we could tell you we found the perfect blueprint for helping millions of people explore purpose at scale. We didn’t. But we did figure out why this problem is harder than it looks.

Our core argument is this: purpose does not scale without standards. And standards do not appear out of thin air. They are produced by whoever holds power and influence.

Historically, that has been the elite’s unspoken job: to model an aspirational life and to justify privilege through visible responsibility. Not perfectly. Not fairly. Often hypocritically. But legibly. Today, elites still hold the power, but they have stopped producing coherent standards — and they have stopped acting like responsibility is part of the deal. The result is not freedom. It is disorientation. And disorientation breeds shame.

For years, we have described the rising tide of anxiety and desolation as a “loneliness epidemic.” But we think a more accurate diagnosis is a shame epidemic: shame born from orienting to a standard that no longer exists — replaced by a flood of competing signals that add up to nothing coherent. Researchers call it prestige bias: people model their behavior, aspirations, and self-evaluation on those who have achieved status and visibility. Across cultures and throughout history, humans have learned what to value by watching those who appear successful, powerful, or admired. Anthropologists have documented this pattern in small-scale societies; behavioral economists observe it in consumer markets; social psychologists see it in adolescent identity formation. We are wired to infer “what matters” from those who seem to win.

When prestige signals are coherent, people may resent them, reject them, or compete within them, but they understand them. When prestige signals fragment, the inference mechanism breaks. People still compare. They still model. But they cannot tell what game is being played.

And when humans cannot decode the game, they default to self-blame.

In our Kenough piece, we argued that weakened institutions leave people without a place to explore purpose. We still believe that. But as we tried to define solutions, we kept circling the same question: Who sets the standard people aspire to in the first place?

The answer is elites. Before you roll your eyes: this is not a love letter to billionaires. We are not defending aristocracy. We are first-gen college grads. We attended K–12 Title I public schools. We benefited from government programs as kids. And yes, we now hold positions of power. If our argument is that standards start with whoever holds influence, then our responsibility starts here — with saying what we think is true, publicly, even when the subject is uncomfortable.

We are not arguing that elite standards are innocent. They have never been innocent. Every standard in history carried violence inside it — what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called the violence of telling people who could not meet the standard that the failure was theirs. But here is where we part company with Bourdieu: the alternative to a legible standard is not liberation. It is what sociologist Émile Durkheim called anomie: the normlessness that arises when shared moral frameworks dissolve. Anomie does not produce freedom. It produces disorientation, despair, shame, and self-destruction.

A society with unjust standards produces resistance, protest, counter-culture. These are oriented forms of agency. You know what you are fighting. A society without standards produces nothing to push against. It just produces drift.

We are not writing a blank check for elites. Standards worth defending must be auditable and visible enough to be debated—revisable, open to reform, and paired with real access and mobility. A standard without a path to meet it is just gatekeeping wearing a different mask.

In this piece, we argue three things:

First, elites have always mattered less for their moral purity than for their ability to produce legible standards and the dominant emotional climate those standards create.

Second, today’s elite failure is different because the most powerful elites now operate in domains—culture and technology—with few institutional constraints, allowing delegitimization to scale faster than responsibility.

Finally, this failure of the modern elite has led to a cycle of chronic shame.

To get there, we track elite power across four domains of power, a recurring cycle of building and burning standards, and the emotional climate each elite period produces.

The Elite and the Masses Over the Ages

“Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God.” The disciples, astonished, ask, “Who then can be saved?” (Matt. 19:25–26; Mark 10:26–27; Luke 18:26–27).

The tension between elites and the masses is as old as time. Their existence has not changed, but their obligation to the public certainly has.

From medieval divine right of Kings to Medici patronage to Regency noblesse oblige to Gilded Age philanthropy, the pattern repeats: power came with a moral job requirement. It was imperfect, often hypocritical, frequently paternalistic, and almost always exclusionary. But it was legible.

Thomas Aquinas systematized natural law to argue rulers had a divine obligation to prioritize their subjects’ well-being. Cosimo de’ Medici funneled banking wealth into orphanages and guild schools while Lorenzo commissioned public chapels—dynastic ambitions alongside genuine civic investment.

The Regency elite revoked Almack’s social vouchers for gentlemen who skipped annual charity assemblies benefiting orphanages and veterans’ homes.

Andrew Carnegie—denied access to a Pennsylvania library at thirteen—later funded 2,509 libraries across the English-speaking world, years before the charitable tax deduction even existed. This was not a tax strategy. It was a stance: wealth carries responsibility. And Rockefeller died having given away the vast majority of his fortune: a reflection of an elite ethic that treated wealth as something to steward, not hoard.

Today, by contrast, much elite giving is deferred, abstracted, or warehoused. Billions sit in donor-advised funds, legally designated for charity but functionally idle. The issue is not that elites give nothing, but that giving no longer functions as a public moral signal or a lived responsibility.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt could have also slipped quietly into private comfort in his Hyde Park estate, funded by family fortune with a few Ivy League degrees hanging on the walls. But public duty was instilled in childhood. His father served as a school board member, town supervisor and church vestryman at St James. At Groton School, his teacher, the Reverend Endicott Peabody, hammered home “service before self” with austere weekly stipends of 25 cents, reducing wealthy heirs to pocket change, along with mandatory trips to mills and farms where children as young as 12 labored.

As a result, FDR built Warm Springs and launched the March of Dimes, inviting strangers to share both struggle and solution. He championed the New Deal: social insurance, public works jobs, pro-labor legislation.

The concept of noblesse oblige was imperfect. Often it was paternalistic, self-serving, exclusionary, and unjust. But it was legible: you knew what power claimed to owe, which meant you could hold it to its own standard or revolt against it. The fact that we still binge Bridgerton, The Gilded Age, and royal-family drama is not nostalgia for the hierarchy. It is nostalgia for the coherence. We are still searching for a visible standard for what power owes.

Who Exactly Are the Elite?

The definition depends on the era. The category has evolved from landed warrior nobility, to merchant-commercial dynasties, hereditary titled aristocracy, industrial titans, technocrats, statespersons, corporate moguls, transnational leaders, and most recently techno-entrepreneurs.

Countless historians, cultural theorists, political scientists, and sociologists have labored over this question. But at its core, elite status emerges at the intersection of multiple forms of power:

Economic: wealth, ownership, resource control, capital allocation

Political / Institutional: Formal authority, decision-making power, state apparatus, law

Cultural / Ideological: Meaning making, legitimation of narratives, prestige, aspiration codes

Technical / Informational: Specialized expertise, knowledge infrastructure, data and platform control

When an individual or group commands enough of these resources, they become what elite theory seeks to explain: the people who set the standard.

And different eras weigh different forms of capital more heavily.

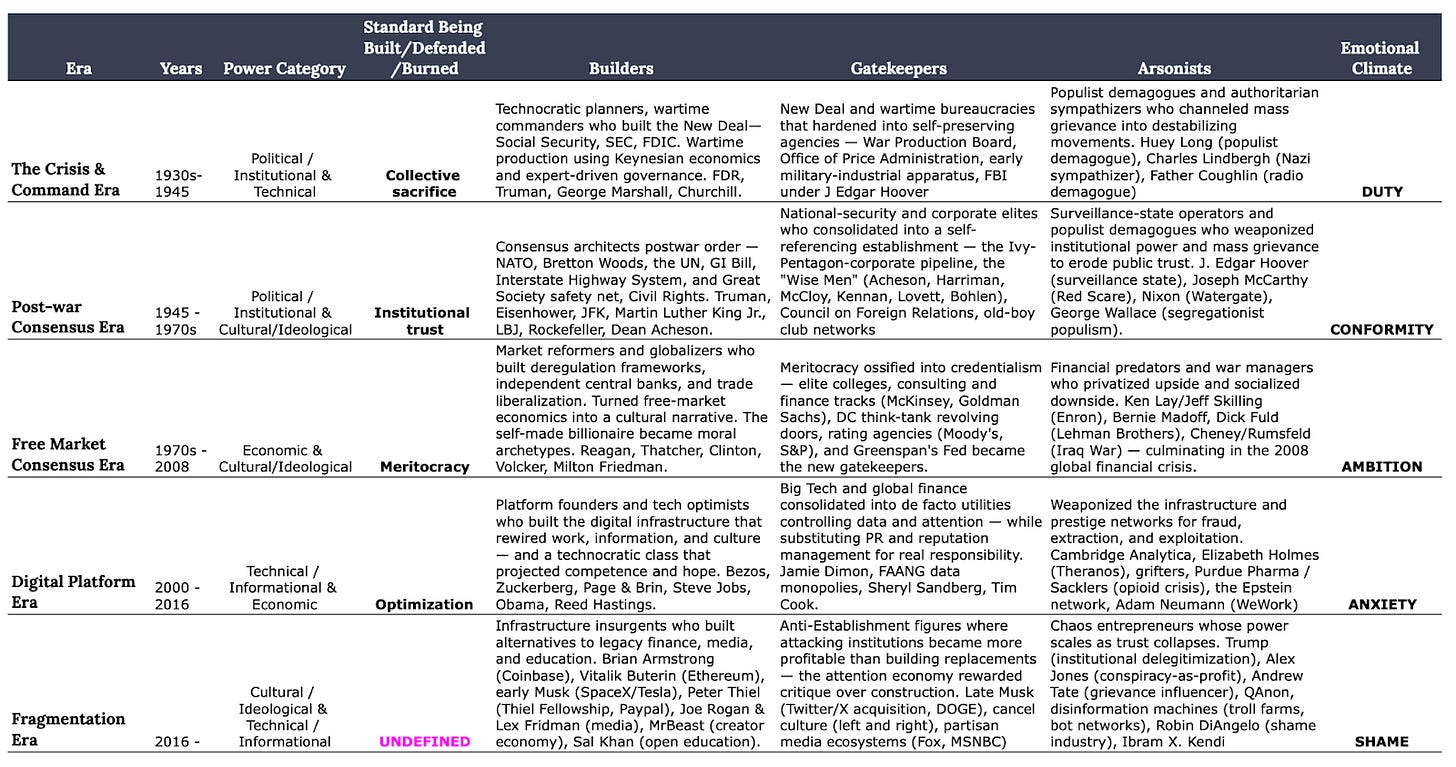

But there’s another layer that matters: elites do not just exist—they tend to follow a cycle. In every era, you can roughly observe three roles:

Builders: create a new standard; legitimacy comes from construction

Gatekeepers: hollow out or ossify the standard; legitimacy comes from protecting the system

Arsonists: burn the standard; legitimacy comes from attacking trust itself

This is not a moral label so much as a structural pattern. Individuals can move between roles. Entire institutions can move between roles. And the same person can be a Builder in one domain and an Arsonist in another. A quick (imperfect) map:

(Yes, this is likely reductive. But it is useful.)

The Failure of the Elite Today

Elites failing to live up to standards is not new. In fact, after studying the last few eras, we are convinced failure is almost guaranteed. Elites calcify. They get insulated. They get greedy. They lose touch. They become self-referential. Then the masses revolt, politely or violently. It is a cycle of accountability.

But today’s failure is different in one key way:

Today’s elites do not even pretend to have a coherent standard they are living up to.

When standards were legible (even if they were unjust) the mass experience was oriented.

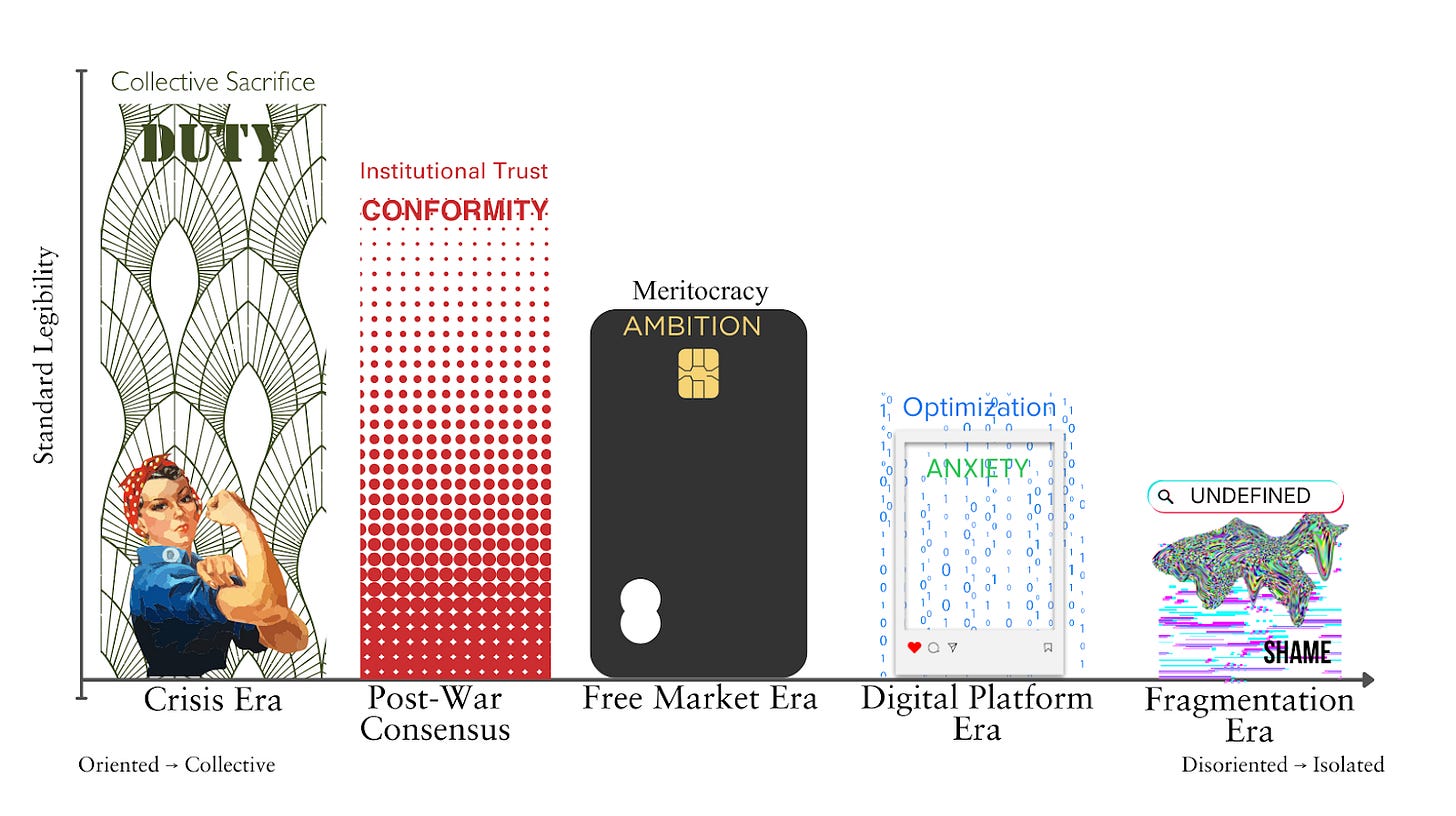

To illustrate this, let’s look at two specific columns in the chart: (1) the standard each era was building towards, and (2) the emotional climate.

Every era’s elite didn’t just hold power: they named a standard. The Crisis Era named collective sacrifice and expert-led recovery as the standard to defend. The Postwar Era built towards cosmopolitan responsibility and institutional trust. The Free-market Era coalesced around meritocracy and individual achievement. The Digital Platform Era strived for competence, optimization, and curated success.

You can disagree with any of those standards. You can critique them as exclusionary, self-serving, or incomplete. But each one was specific enough to orient to. And the emotional climate of each era tracks accordingly.

When the standard was collective sacrifice, the emotional climate was duty — you knew what was asked of you, and the ask was shared. When the standard was institutional trust, the experience was conformity — rigid and exclusionary, but legible enough that even nonconformists knew exactly what they were pushing against. When the standard was meritocracy, the focus was ambition. The rules were visible, the ladder was climbable, and the gap between where you were and where you wanted to be was the incentive.

Then something shifted.

When the standard became competence and optimization in the early 2000’s — curated, algorithmic, performed through Instagram grids and TED Talks and LinkedIn branding — the experience for most became anxiety. You sensed you were falling behind, but you couldn’t name why. The ladder was still there, but the rungs had gone invisible.

And then the standard disappeared entirely. When the Fragmentation Era’s standard column is UNDEFINED it’s not because we’re being cute, but because no one can name what it is. Because the elite have failed to provide a coherent standard.

The resulting experience is shame. Not anxiety about falling behind on a known standard, but the corrosive feeling of failing against a standard you can’t even identify. The platforms are free, frictionless, the tutorials are everywhere, the tools are open to anyone, so when the life they promise doesn’t materialize, there’s no gatekeeper to blame. Failure feels personal. And when shame can’t be named, it converts to the only thing that offers relief: rage, blame, and grievance. Every Arsonist in this era offers an external target for internalized shame.

That arc — duty, conformity, ambition, anxiety, shame — is not random. It tracks the progressive illegibility of elite standards. As the standard became harder to name, the emotional experience shifted from oriented to disoriented, from collective to isolated, from outward to inward.

We are not arguing that these were the only emotional experiences of each era. Nor that prior decades were free of despair. Rather, each dominant elite standard created a primary orientation pressure: a widely shared emotional climate that shaped how people interpreted success and failure.

As standards fragmented, the emotional climate shifted from collective to individualized. From external duty to internal evaluation. From “Are we living up to our shared obligation?” to “Why can’t I measure up?”

The Beginning of the Elite Breakdown

The Depression and WWII led to the rise of technocrats, which made sense. Turbulent times require planners. The New Deal produced massive reforms and real institutional strength. But that investment also created bureaucracies incentivized to preserve itself.

Then came the Free Market era — globalization, deregulation, and the gospel of meritocracy, promoting the idea that anyone could make it if they worked hard enough. And for a while, it delivered. Dropouts, children of immigrants, and people from humble beginnings built real enterprise value and took positions of power.

But then meritocracy mutated into credentialism, which was just a new kind of gatekeeping. Elite status became increasingly defined by credentials, funnel access, and résumé signaling. This era trained young people to believe that getting into the Goldman Sachs or McKinsey analyst class was not just a career step, but a moral achievement.

Credentialism created four problems:

It locked many people out, only worsened by income inequality;

The ROI of college degrees declined, leaving aspirational people feeling cheated as they did everything they were “supposed to do” but were left with mountains of student loan debt and underemployment;

It produced cookie-cutter elites optimized for “checking boxes” not thinking creatively;

It replaced building with signaling.

Then we arrive post the 2016 election. Credentialism didn’t just create a new gatekeeping class. It created a structural trap. The system kept producing more and more people with the credentials, the ambition, and the self-image of an elite — more law degrees, more MBAs, more would-be founders and senators — than it could ever absorb into actual positions of power. A game of musical chairs where we kept adding players but never added seats. The historian Peter Turchin calls this elite overproduction, and he predicted a decade before 2020 that it would produce exactly the instability we’re living through.

But here’s what connects this to the shame epidemic at the center of our argument: popular immiseration — the declining welfare of ordinary people - isn’t just an economic condition. It is the psychological experience of being told the ladder is climbable while the system extracts everything you have. You did the degree. You took the debt. You checked the boxes. And the door stayed shut. Shame is the residue of that structural betrayal: the gap between the meritocratic promise and the rigged reality.

Elite overproduction provides the match. Mass shame provides the fuel. And when match meets fuel, you don’t get reform. You get Arsonists.

The Fragmentation Elite of the 2020s

The 2020s are defined by what we’ll call the fragmentation elite. These are figures whose power flows primarily through culture and technology, the two domains with the fewest institutional constraints. Some built. Some gatekept. Some burned. But all of them operated in spaces where no one had the authority, speed, or legitimacy to say no.

At first, this produced something genuinely constructive.

Platform founders like Bezos and Zuckerberg were the original Builders. They created infrastructure that bypassed legacy gatekeepers in retail, media, and communication. But by the 2020s, they had become the new establishment. The Fragmentation Era’s own Builders looked different: Armstrong and Buterin in decentralized finance, Rogan and Fridman in independent media, Khan in open education, Mr.Beast in creator-driven entertainment. Their legitimacy came not from building platforms inside the system, but from building alternatives outside it.

It’s important to say this clearly: the fragmentation elite rose in response to real institutional failure. Higher education had become increasingly expensive and disconnected from outcomes. Media credibility was collapsing. Financial institutions appeared insulated from consequences and transparency. Political systems felt captured by a few and unresponsive to most.

You saw this impulse not just in tech platforms, but in institutional experiments. Reed Hastings helped fund the charter school movement in response to a failing public education system. Peter Thiel launched the Thiel Fellowship as a critique of credential inflation in higher education. Whatever one thinks of these efforts, they shared a common logic: if institutions no longer work, build alternatives.

But over time, Builders gave way to Arsonists — figures whose influence came not from building alternatives, but from eroding trust in existing systems. Elon Musk’s promotion of Federal Government DOGE illustrates this turn: enormous cultural traction generated not by offering a viable alternative to federal bureaucracy, but by publicly questioning the legitimacy of governance itself and signaling contempt for it.

And from these delegitimizers came the most dangerous mutation: elites who harness discontent not to build durable civic capacity, but to accelerate discord itself. They profit from institutional decay. Their power scales as trust collapses.

They don’t offer standards. They offer grievance.

They don’t model duty. They model domination.

Donald Trump is the clearest example. He is a political actor whose power derives from delegitimizing courts, elections, media, expertise, and shared truth. But the dynamic isn’t partisan. It appears wherever outrage becomes legitimacy and attention replaces responsibility. You see it in political media figures on both sides, activist entrepreneurs, and cultural elites who convert fragmentation into personal brand power.

In a functioning system, elites are constrained by norms. In a broken system, chaos itself becomes the asset.

And we can’t talk about the failure of the elite without discussing the Epstein case and its aftermath. Not because of the horrific crimes themselves, but because of what the case revealed about elite culture: a system in which exploitation could persist for years, warnings could be ignored, accountability could be delayed or dissolved, and consequences could be unevenly applied depending on status.

For the public, Epstein wasn’t experienced as an isolated failure. He was experienced as confirmation of something more corrosive: that there is one moral code for those with power and another for everyone else. Standards exist, but only downward. When that realization takes hold, aspiration curdles. If the people setting the standard don’t live by it, the standard itself loses legitimacy.

Why This Era Is Structurally Different

In every previous era, the dominant forms of elite power had institutional checks built into them. Nixon was impeached. Enron collapsed under SEC scrutiny. The 2008 crisis, however inadequately, triggered regulatory response. These constraints were never perfect. But they existed. There was something and someone whose job was to say no.

Here’s what makes the Fragmentation Era different from every one that came before: the two dominant forms of elite capital — cultural/ideological and technical/informational — are the two least constrained by institutional norms. Political power has elections. Economic power has regulators. But who governs meaning? Who audits the algorithm?

Today’s most powerful elites set standards through platforms and narratives that no institution has the authority, speed, or competence to check. The result is exactly what we’d predict: not just elite failure, but elite failure with no correction mechanism. Standards don’t just decline. They fragment. And fragmented standards don’t produce counter-culture — they produce confusion. And confusion, as we’ve argued, produces shame.

Worse, the Builder-to-Arsonist cycle now collapses inside a single career. Musk built Tesla and SpaceX, then turned to institutional demolition through Twitter/X and DOGE. Thiel funded Builders through the Thiel Fellowship, then bankrolled political destruction. Rogan built the largest independent media platform in modern history, then became a distribution channel for the very conspiracy thinking he once challenged.

The question isn’t whether Builders exist. It’s whether they can stay Builders long enough to institutionalize what they’ve created — before the attention economy converts them into the next generation of Arsonists.

Okay, But Why Does Elite Failure Matter for Purpose?

Thank you for hanging in with us. Here’s where we land the plane.

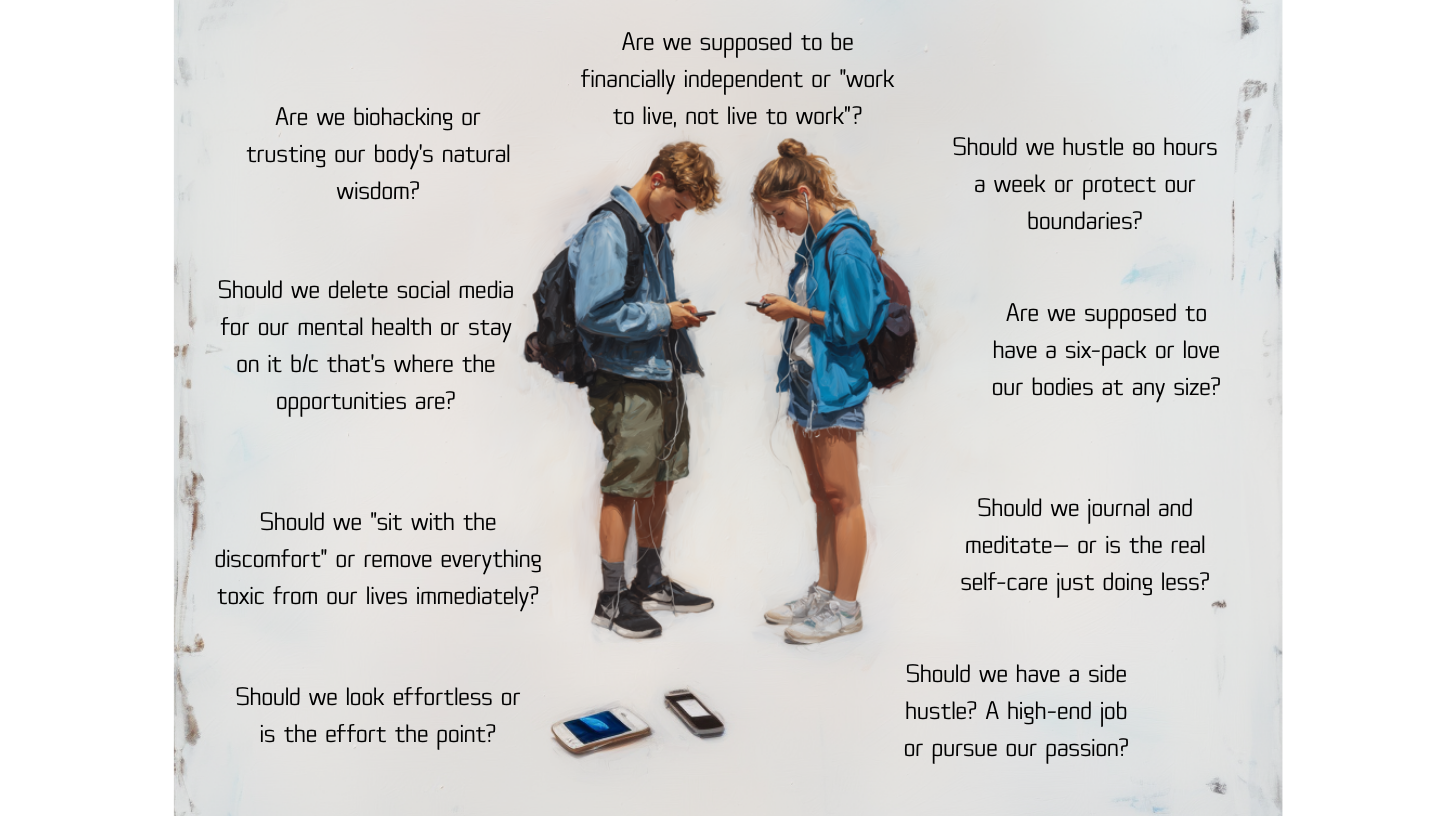

Our argument is that the masses look to elites to define the aspirational standard. Without that standard, people feel aimless. And so, they engage in a vicious cycle of shame.

Historically, elites have defined what we should aim for: fashion, values, religion, civic engagement, family structure, and what “respectable” means. That doesn’t mean everyone accepts it. Counter-culture exists because people reject it. But having a standard to react to is critical.

With a clear standard, you have an end goal and can measure whether you’re getting closer. But when the benchmark is vague, inconsistent, a moving target, and pieced together from Instagram, podcasts, influencers, and self-help aisles, it becomes confusing at best and dangerous at worst.

Are we supposed to be financially independent by 30 or “work to live”?

Are we supposed to have a six pack or love our bodies at any size?

Should we have a therapist? A side hustle? A high-end job or pursue our passion?

Should our style be old money cool, coastal grandmother, or boom boom?

This form of confusion can lead to extreme and dysfunctional coping mechanisms like looksmaxxing where young men are so desperate to be deemed desirable that they are willing to break their own bones. Or worse: so frustrated with the state of relationships and predatory dating apps that they choose to self-identify as an incel.

The shame of failing to meet an undefined standard is corrosive. It breeds cynicism, nihilism, burnout, and distrust. And perhaps worse: it breaks the social contract that encourages belief in progress and aspiration in the first place.

The strongest objection to our argument is that this is not about elites at all. It is about economics. Or technology. Or globalization. Or the inevitable chaos of a hyperconnected world.

We agree those forces matter. But they do not explain the psychological pattern. Shame emerges when individuals internalize failure against a promise they were told was achievable. And that promise of meritocratic mobility, optimized self-actualization, frictionless opportunity was articulated and amplified by those holding power.

This is why elite coherence matters. Not because elites are morally superior. But because they define what counts as success in the first place.

We believe what has been described as the “loneliness epidemic,” is not loneliness at all. Because loneliness is an adaptive signal — it pushes people toward connection.

What we’re seeing instead is withdrawal. People are disengaging. Opting out. Numbing. Retreating from ambition, relationships, and civic life.

That pattern aligns more closely with chronic shame.

A lonely society seeks connection.

An ashamed society seeks escape.

Stay tuned for Part II where we discuss the solutions.